Seven moats for energy transition startups

Moats allow companies to keep away competitors and increase their profit margins. Understanding possible moats helps with evaluating startup strategies and finding the weaknesses of incumbents.

Background

I want to understand the strategic choices that successful startups make to win markets. My articles discussing moats or pricing strategies are parts of this exploration. A friend told me that “7 Powers: The Foundations of Business Strategy” is a favorite of Peter Thiel and the Founders Fund universe (Fig. 1). I have read the book and been impressed with the insights and the framework. The book first defines Power as “the set of conditions creating the potential for persistent differential returns.” This definition is similar to the concept of a “moat.” The book then defines strategy as “a route to continuing Power in significant markets.” The book explains that the two most important attributes of Power are the magnitude and duration of the differential returns. In this article, I present these seven types of moats with examples of startups in the energy transition.

Moat 1 – Scale economies: Northvolt

A “scale economies” moat is “a business in which per unit cost declines as production volume increases.” Certain fixed costs like engineering design or marketing remain constant regardless of the number of units produced. The per-unit cost of these activities decreases at higher volumes. The book argues that this relationship can be an effective moat for different businesses. New entrants would lose money if they produced at lower volumes, which would dissuade them from entering the market. Scale economies can act as a moat in other contexts as well. For example, the distribution network density of UPS and the purchasing economies of Walmart act as a barrier to new entrants into their respective markets.

Northvolt is an automotive battery manufacturing startup that is building such a moat. The company was founded in 2015 and it has raised $9B. Northvolt does not have a differentiated technology, business model, or distribution network. However, it entered the market when there were few European automotive battery startups. It picked an already-established technology and scaled rapidly to reach a valuation of tens of billions and 4400 employees within just eight years. TechCrunch reports that Northvolt has “Secured more than $55 billion in orders from customers like BMW, Fluence, Scania, Volvo and Volkswagen.” The founders of Northvolt were previously supply chain executives at Tesla. They both had experience building large organizations. The scale of Northvolt means that the European market will likely not see another entrant unless the startup aims for a different type of moat.

Moat 2 – Network economies: Dandelion and Rana Energy

A “network economies” moat is “a business in which the value realized by a customer increases as the installed base increases.” This type of moat has dominated consumer software for the past two decades, especially in social networks and two-sided marketplaces (Uber, Facebook, Venmo, etc.). In this scenario, individual users benefit from the large number of other users on the platform, which disincentivizes them from moving to a new and less popular one.

I had trouble thinking of many energy companies that have a network economies moat. Such moats are most associated with consumer media or service businesses where there is little transactional friction. The energy sector is highly regulated, which increases transactional friction. In addition, services often depend on large infrastructure like the electrical grid or major companies like electricity suppliers and not just individual consumers or service providers. The first business model of Dandelion Energy depended on network economies. The company was a two-sided marketplace that connected homeowners with independent contractors capable of installing geothermal heat pumps. The company has since changed that model and now employs the workers directly.

Rana Energy plans to build two-sided marketplaces for electricity production, storage, and consumption on residential microgrids in Nigeria. Developed countries have historically built their infrastructure around producing electricity centrally and distributing it to individual homes (Fig. 2). The distributed storage and solar production now available can conflict with this centralized model. Many developing countries leapfrogged landline telephones and directly adopted cellular phones. Rana wants to repeat this leapfrogging for decentralized electricity. It plans to build a two-sided marketplace for electricity where individual households can buy and sell electricity from each other on a microgrid. Such a two-sided marketplace is possible in a developing country where less infrastructure and regulation reduce transactional friction.

Moat 3 – Counter-positioning: Sunrun

A “counter-positioning” moat forms when “a newcomer adopts a new, superior business model which the incumbent does not mimic due to anticipated damage to their existing business.” Counter-positioning is not the same as a disruptive technology. A disruptive technology "does not necessarily lead to… [a moat], but it can sometimes create the circumstances in which… [a moat] may be established.” Counter-positioning is about a new and better business model that the incumbents ignore until it is too late.

Sunrun (founded in 2007 and market cap of $2.1B) has revolutionized the residential solar market by helping customers buy electricity through power purchase agreements (PPAs). In the past, homeowners who wanted solar energy had to pay for the system upfront (~$50k in 2008). Instead, Sunrun owns the panels for ~20 years and sells electricity to the homeowners at a fixed rate over that period. Offering financing, and especially PPAs, for purchasing home solar and battery is now the dominant business model in this sector. SunPower, Sunnova, and Vivint Solar all offer multiple options. Sunrun’s approach has been adopted by other home energy solutions. For example, Dandelion partners with banks to provide financing for its geothermal heat pumps. This business model innovation has contributed to a 100X increase in the annual residential solar capacity installation in the US since 2007.

Moat 4 – Switching costs: Terabase

A “switching costs” moat is “the value loss expected by a customer that would be incurred from switching to an alternate supplier for additional purchases.” The author presents “SAP’s [market cap of $167B] paradoxical combination of high retention and low satisfaction” in the enterprise resource planning software (ERP) space. Fundamental company operations like receiving, tracking, and fulfilling orders rely on ERP software. It is risky and expensive to switch ERP systems after adopting the software, integrating it into the organization, training employees on it, and building relationships with the vendor. Most companies choose to stay with SAP and even purchase additional tools from them to avoid this risk. These high switching costs act as a moat for SAP.

Terabase (founded in 2019 and raised $77M) is building a suite of software tools for the development, construction, and operation of utility-scale solar power plants (Fig. 3). Their tools look useful, but I do not see radical technical advancements that would provide a technology moat. Altogether, the software suite reduces the cost of building and operating these facilities. I like their creative product strategy. Some companies sell solutions for a single area and then convince the user to buy their adjacent product offerings. For example, if a customer buys an order tracking solution, they may also purchase an adjacent solution to predict restocking needs. Terabase products are adjacent in time. If a customer uses Terabase for the development of a new plant, they will be incentivized to purchase additional tools for the subsequent construction and management phases. Terabase’s moat is based on this desire to avoid switching costs.

Moat 5 – Branding: Span

A “branding” moat is “the durable attribution of higher value to an objectively identical offering that arises from historical information about the seller.” A branding moat builds over time, as the company delivers a high-quality product and builds trust. Consumers buy branded products to associate with a particular identity and reduce the uncertainty in their purchasing decisions. After building a branding moat the company can charge a premium for its product.

Span (founded in 2018 and raised $230M) is building a branding moat around its smart electrical panels. I have written before about how Span used a significant portion of its $3.5M seed round on industrial design. Arch Rao, the founder and CEO of Span, said that,

It's very unusual for a seed-stage company, with a few single-digit millions in the bank, to go spend money with an external industrial design company. But from the very beginning, it was super important to us to build a… hardware and software product that was stunning, and I think we’ve achieved that.

Span’s panel looks symmetric, sleek, and compact compared to the product from Square D (Fig. 4), a subsidiary of Schneider Electric (founded in 1836 and a market cap of $88B). It offers convenient features like lights on the sides of the panel to increase visibility. Finally, there is a large company logo at the top of the panel, just as Apple products prominently display their logo. All of these features point to a branding moat around a luxury product. Interestingly, both companies charge $3,500 for their panels. I think there are two reasons for this decision. First, according to the author the ability to charge customers a branding premium forms over time. Second, these electrical panels are intended to last for decades and have high switching costs. Span can generate revenues from selling services and software after the hardware installation. This future revenue incentivizes the company to lower the barrier to initial adoption.

Moat 6 – Cornered resource: KoBold Metals

A “cornered resource” moat is “preferential access at attractive terms to a coveted asset that can independently enhance value.” A cornered resource may be physical, like exclusive access to raw materials. The resource may be technological, like exclusive rights to intellectual property (IP). The resource may be regulatory, like a license from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), which has not been granted in half a century. The resource may simply be information. Many artificial intelligence (AI) companies build “data moats” that ensure them the best-trained models compared to competitors. Companies can even corner human resources by hiring the best in a particular field. The compensation of individuals with in-demand skills increases dramatically as companies compete to hire them. A typical engineer at OpenAI (maker of ChatGPT) earns $1M annually.

KoBold Metals (founded in 2018, raised $400M, with a valuation of $1.15B) is building multiple of these moats. The company trains AI models on geological and Earth observation data to discover and develop metallic mineral deposits. These metals are critical to the energy transition. The company’s AI models are proprietary, which is one cornered resource. It has received investment from the oil company Equinor, partly to gain access to their geological data, which is another cornered resource. Combining these resources and the investment from Andreessen Horowitz I expected that they would have a SaaS business model. However, they take a stake in their mineral finds, jointly develop the mine with partners, and generate revenue from selling metal. Mineral rights are another cornered resource. Experts in this field have told me that companies relying only on discovery can be squeezed easily, but those with mineral rights have much more power.

Moat 7 – Process power: Tesla

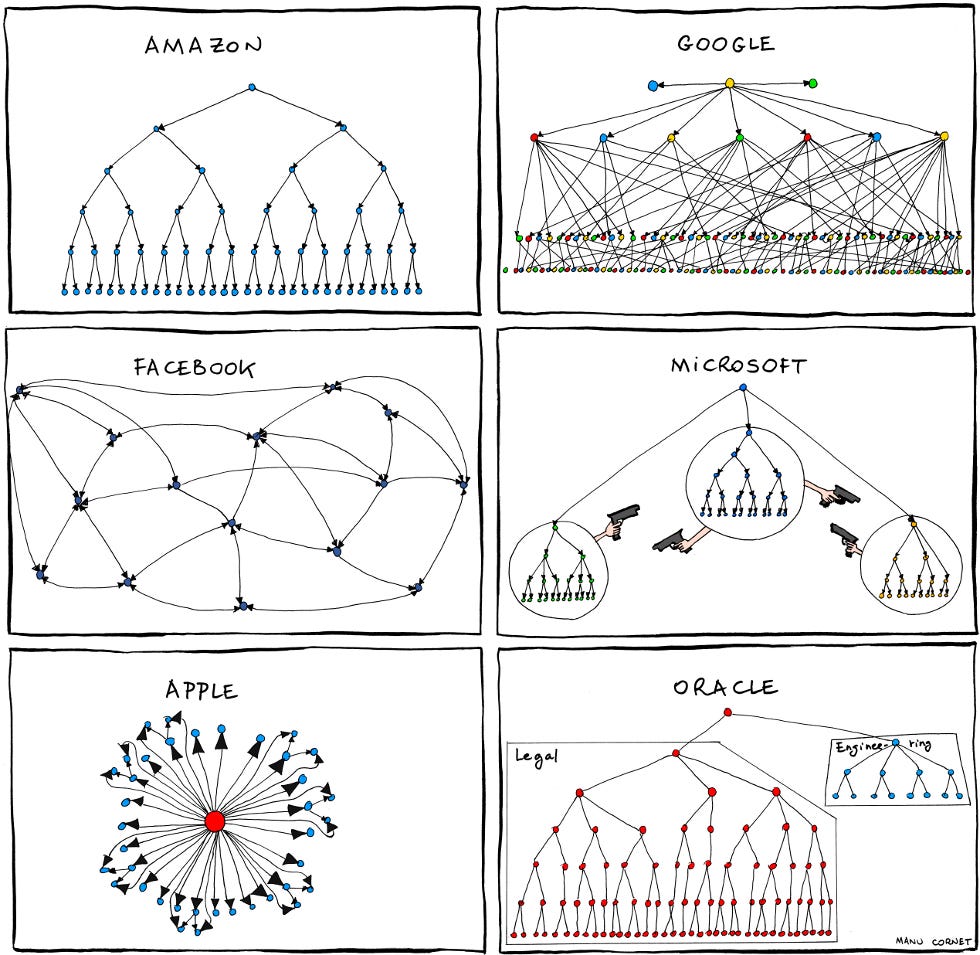

A “process power” moat is “embedded company organization and activity sets which enable lower costs and/or superior product, and which can be matched only by an extended commitment.” The author emphasizes that this moat is not merely operational excellence, which can be mimicked. This power captures the unwritten ways that organizations operate and those within them relate to each other. These relationships may allow companies to gain a sustained advantage over time. I think this moat is akin to “company culture.” Even companies with nominally the same organizational structure often operate differently based on their cultures (Fig. 5).

The book uses the example of the NUMMI plant in Fremont, CA. NUMMI was jointly operated by GM and Toyota starting in the 1980s so that they could learn from each other. Toyota was able to gain from this experience, but GM executives had difficulty replicating the Toyota Production System (TPS) in other plants. Tesla took over that Fremont plant in 2010. Tesla is large enough and old enough to have built a process power moat. Employees often point to the intensity, personal responsibility, and pace of change at the company. A former Tesla engineer told me that “Tesla [59k employees] is a big company that moves like a startup.” These characteristics are part of the reason that Tesla has a process power moat (among other moats). Tesla has a price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio of 67, which is an order of magnitude larger than that of GM (3.9), Ford (4.6), and Toyota (11).

Discussion

These moats operate on a different plane than the dual framework of technology and business moats. For example, Northvolt’s scale economies is largely technological, whereas Walmart’s scale economies is a business moat based on purchasing power. Companies can also build moats in multiple categories. For example, Tesla has a counter-positioning moat (direct sale to consumers), a branding moat (luxury product), a cornered resource moat (preferred access to battery materials), as well as a process power moat.

Investors, employees, and strategists need to be aware of these categories. A former executive who previously ran a large organization may be more successful in building a scale economies moat. Instead, a founder pursuing the cornered resource of exclusive IP may benefit from a deep technology background. Traction must be measured somewhat differently in each category. Companies pursuing scale economies may quickly raise capital and grow their teams. However, this rapid expansion may be the sign of an undifferentiated product that scales unencumbered by technology development. A differentiated technology may provide a better long-term moat than a highly scaled one.

These categories are important for thinking through market dynamics. It is likely too late to build another European battery company aiming for a scale economies moat. The newcomer would find it difficult to compete with Northvolt. However, a newcomer with exclusive access to IP, raw materials, or even one with a novel business model may still be viable. According to Richard Rumelt, “strategy is the application of strength against weakness.” It is important to know where the incumbent is strong for the newcomer to avoid that territory.

Question

What is your favorite moat and which company is a good example of this moat? Tell me in the comments!

A song I like

"Everything will disappear but The wind will carry us"

Hot pilates beat

Featuring Idris Elba (aka Stringer Bell)

A scene I like

Hannibal Lechter: “He covets. That is his nature. And how do we begin to covet, Clarice? Do we seek out things to covet?… No. We begin by coveting what we see every day.”

As always, covering complex topics in a simple yet elegant way!

What if another company sell a moat to other companies? Can it be possible? Especially if that one is 7th one?